Dear Trump supporter

He’s no Obama. But it was a good speech. I’ll give you that. Or maybe I should say, it was the speech that you needed to hear.

I can see the hope in your faces. The hope that in Donald Trump, you’ve finally found a Fixer-in-Chief. That he will be able to bring back American jobs. That he will restore America’s standing in the world. That he will make America feared and loved, and Great, once more.

I get why you’ve put your faith in him. I see what he inspires. There is some truth mixed in with the drivel. On corruption. On political correctness. On losing your status in society. I feel your rage because the system feels unfair and unjust to me too. I know that slow-burning anger that has been building up over decades. Because, let’s face it, you have been betrayed by your political leaders, on the left and the right. Your Congress and your politics is so broken that you’re desperate to try anything. I get it.

Trump feels like your last chance- your best hope at turning back time to an era when there was certainty that if you did what you were supposed to do, you’d be able to buy your own house, live in a safe neighborhood, and send your kids to a decent school. That promise of the American dream is dying.

It used to be that if you were smart and worked hard, you could slowly climb your way to the top. These days, the chances of that happening are unlikely. Kids who were born in the poorest 20% of US households have a 7.5% chance of making it into the richest 20%. In Canada, if you are born in the bottom 20%, you have a 13% chance of moving into the richest 20%. The American myth that anyone can make it…. well, it just doesn’t apply anymore. That part of the social contract has been broken.

Those who have been in charge of your government- including Democrats, especially Democrats- should be kicking themselves today. Because it was our politicians who let this happen. But they didn’t do it by themselves. We, the voters, also let this happen.

But I want to tell you something else. Something that politicians of all stripes are too scared to tell you.

The truth is that those jobs aren’t coming back to the US, the UK, or any rich OECD country. And it’s not all because of China either. Globalization, automation, and now artificial intelligence– these factors are as much to blame as China’s WTO ascension and their economic espionage.

The forces that created that cheap and powerful iPhone in our pockets are the same ones that are vastly increasing inequality within the US. You can’t have your iPhone and eat it too. But that’s what Donald Trump is promising you.

I hope we can at least agree that Donald Trump discriminates against women and minorities. Maybe you recognized this, and voted for him anyway.

But what you may not realize is that his divide-and-conquer strategy will harm the foundations of American democracy. Because the thing that makes America truly great- its openness and embrace of newcomers from all over the world- is slowly being replaced by fear and paranoia about those who are different in any way.

For the past 6 months, I’ve been watching President Trump destroy his opposition piece-by-piece using this strategy.

So far, he has co-opted his strongest opponents by pretending to placate them- witness one Mitt Romney who was wined and dined by candlelight at Trump Tower. And every single one of his opponents has fallen for it. Masterful.

Inside the Democratic Party, he has created rancor and division without doing a thing- What to do? Resist, fight back, co-operate where possible? He is also destroying the credibility of all opposition in the mainstream media- which has done itself no favors by idiotically hanging on his every tweet. CNN now has #fakenews as part of its byline thanks to President Trump.

Maybe you think that they, all of them, deserved it. But trust me- this isn’t what you want. Because one day, he will break his promises and turn on you too, and there will be no one left to speak up for you and your family.

Colombia: Use the Truth Commission to Open up the Peace Process

By Christine Cheng and Charlie de Rivaz

Published in La Semana (a major Colombian magazine) on July 8, 2016. En español aquí.

Summary: With the Colombian government and the FARC on the brink of signing a final peace agreement, it is time to open up what has so far been a closed process. A step in the right direction would be to place the principles of public consultation and community outreach at the center of the process for selecting Commissioners for Colombia’s Truth Commission.

Last week, the Colombian government and the FARC reached a deal on a bilateral ceasefire, paving the way for a final peace agreement to be signed. Despite the fact that all of the concluded peace agreements are publicly available, Colombian citizens have had very little say in the negotiations. The peace process has largely been conducted behind closed doors in Havana. While the need for secrecy was understandable when the peace talks first began, the government now needs to win the support the support of the public. The process must be opened up or else the government will lose public support for whatever deal is reached, along with the proposed referendum on that deal.

It has taken almost four years to reach this point. With the promise of a referendum on the final peace agreement, the government must begin to address the public’s concerns. How can society ensure that those responsible for past abuses are held accountable? How will Colombians enforce justice while aspiring for reconciliation after suffering through half a century of violence? Colombians remain deeply divided on how they believe justice and reconciliation would best be achieved.

But the one thing that Colombians do agree on is the need for truth. Without truth, there can be no justice and reconciliation. Victims of human rights abuses and serious violations of international humanitarian law deserve to know what happened to them, who did it, and why they did it.

Colombia’s Truth Commissioners will be chosen by a nine-person Selection Committee, which will seek nominations from around the country and abroad, and then spend three months vetting the candidates and making its final selection. Unfortunately, the agreement offers precious little detail about how the selection process will work in practice. We have written a report – published this week – that offers ideas for choosing Truth Commissioners at each stage of the selection process. Our report draws from the range of experiences of truth commissions in other countries, and builds on the legacy of Colombia’s National Center of Historical Memory.

The process for selecting Colombia’s Truth Commissioners provides an important opportunity for President Santos and Sergio Jaramillo, the High Commissioner for Peace, to open up a peace process that many have felt was closed off from public scrutiny. To do this successfully, public consultation and community outreach are key. The selection process must not be dominated by the elite. Rather, the process must reach all parts of Colombia, especially the areas that suffered the most violence.

Truth commissions in other countries demonstrate the importance of public engagement in choosing commissioners. In Kenya, the selection committee did not seek feedback from the public before it made its final selection. Had it done so, it would have become clear that the proposed chair of the truth commission, Bethuel Kiplagat, was unsuitable for the job because of his alleged complicity in gross human rights violations. The controversy prompted the resignation of the truth commission’s vice-chair, Betty Murungi, and irrevocably undermined the legitimacy of the commission. A lack of consultation with the public similarly damaged the 2003 truth commission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Of course, genuine public consultation takes time, and there is a danger that the public may lose patience with the selection process if it takes too long. As such, a balance must be struck between leaving sufficient time for consultation and maintaining the momentum of the peace process. But opening up the process is key. First, it will empower and educate ordinary Colombians. By giving the public the chance to nominate candidates for Commissioner or allowing them to follow the interview process, the public will become more vested in the peace itself. At the same time, public conversations about the candidates will bring about a greater sense of public ownership of the Truth Commission and, by extension, the peace process itself.

In Sierra Leone, after the initial selection process stalled, publicly re-advertising the truth commissioners’ positions educated the public about the role and importance of the commission and the qualities needed to become a commissioner. In Timor-Leste (2002) and South Africa (1994), the interview process for the shortlisted candidates took on the form of public hearings, which gave the public a greater sense of ownership over the process.

An open selection process would provide yet another entry point into the national conversation about the peace process – further opening up a space for civil society to question, to debate, to criticize – and to set the tone for the post-conflict transition. Undoubtedly, powerful factions will express their anger and frustration with the peace process, but allowing these protests to be aired is important. While the political ruptures this conversation provokes may be destabilizing in the short run, Colombia’s peace will ultimately be more robust in the long run.

Of course, there is the danger that the selection process and the Truth Commission itself will be seen as political instruments rather than instruments of societal healing. If these are viewed as a way of doing the president’s bidding, and the Commissioners are not viewed as independent from the government, people will not come forward to testify and the process will lead to political disaffection.

The truth process is an important mechanism for restoring balance to society. It will give victims a voice, let perpetrators apologize, and bring closure to families who have long wondered what happened to their loved ones. Colombia’s truth commission will write the story of a war that began over five decades ago. Choosing the right people to lead the process of truth-telling will determine whether or not this will be an honest process. The Truth Commissioners will set the tone for the kind of peace Colombians want to enjoy, and the kind of society that Colombians want to live in. Here is a clear opportunity for the president and the FARC to define a path of integrity for the new Truth Commission, and for the country. They must seize it with both hands.

* * *

For a full discussion, please read our CSDRG Policy Brief, Colombia- SelectingTruthCommissioners. En español aquí Colombia-SeleccionDeComisionados.

Charlie de Rivaz is Editorial Assistant at Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), and a graduate of the Conflict, Security, and Development program at King’s College London.

Special thanks to Sofia Liemann and Paola Ferrero Moya for translation assistance.

Why we teach

If you’ve ever taught, you know how rewarding it can be. The transformation can seem almost magical sometimes as you watch students stretch themselves intellectually, week after week, term by term. You can feel the progress and its accompanying struggle, as students eke out their gains, reading by reading, one problem set at a time. You listen as they experiment with different viewpoints, trying each one on for size. And you fight the urge to jump for joy when you see them nail it- a presentation, an essay, a moment of insight. This is undoubtedly one of the most gratifying parts of my job as an academic. It feels good when you know that you’ve taught them well- even when they can’t yet appreciate it for themselves.

Then there’s the icing on the cake: every once in a while, you receive an out-of-the-blue heartfelt thank you. An unexpected visit from a student you haven’t seen for years; gifts in your mailbox (like my favourite polkadot teapot); or a thank you note that comes months or years after the final lecture, long after the diplomas have been awarded. Recently, I received one of these thank yous and it brought me a lot of joy. After some thought, I asked my student if I could share her words.

Dear Christine,I hope this finds you well.I never got around to emailing you after the dissertation frenzy, but they say it’s better late than never.First of all, I wanted to thank you for the dissertation support. I learned a lot and was pleased to notice that both you and Dr Patel mentioned my evident enthusiasm for the topic and that you appreciated my effort to critique the dominant Anglosaxon perspective- I found that feedback perhaps more important than the grade itself.I also wanted to thank you for your class on state failure, and for the CSD [Conflict, Security, and Development] lectures. You always brought a ‘fresh’ perspective and attitude to class, and amongst the other lecturers, the fact that you had had extensive experience working in the field was evident and brought much appreciated pragmatism to our discussions.Shortly after handing in my dissertation last summer I began interning at WFP [World Food Programme] HQ in Rome, where I have been since. Coincidentally, I applied at a time when they were setting up various civil-military projects. The fact that I had written a dissertation on this topic meant that I had background knowledge in a subject that both humanitarians and militaries generally prefer to avoid!So far I have been loving my job at WFP- I’ve been working in the Emergency Response division and I have learned so much. I have so much respect for the work that is done and the hardworking people that have committed their lives to making our imperfect humanitarian system a little less imperfect.There are days where, inevitably, I have flashbacks to the CSD/SF [state failure] discussions and moral dilemmas- to your class, to the dominant conclusion to many of our questions: ‘Well, it depends’. I also think a lot about our discussions and what many of you, as teachers, as well as us students were very aware of: that the reality on the ground is so different from what we read about in books. This is clear in my work at WFP headquarters. As much as we try to design the best options for field conditions, the reality is that those who have to implement these plans will encounter obstacles that we, from the ivory tower perspective, will not be able to take into account.Anyways, I think I’ve gone on for too long! I really do hope this finds you well and I just wanted to thank you for your class and your teaching. Oh, and you were right about sharing food in class- it really does bring people together.Best,CB

I teach- we all teach- for moments like this. It’s a reminder to all of us teachers that our words and ideas continue to resonate in students’ minds months and years later…. long after they’ve left our classrooms.

War Studies is hiring *7* permanent/tenure-track faculty, 18 posts in King’s politics

Yes, that’s correct. The Dept of War Studies at King’s College London is hiring 7 permanent lecturers + 2 fixed-term lecturers. In addition, Defence Studies (Shrivenham campus) is hiring 8 permanent lecturers, and there are 3 more permanent posts in International Development.

For those who are not from the UK, these are tenure-track positions equivalent to assistant professor. WS is a huge interdisciplinary department (70? tenure-line academics + 50? research associates, teaching fellows). We welcome scholars in history, politics & IR, psychology, geography, area studies, anthropology, sociology, economics, computer science, law.

For more on why you should apply, see here for my sales pitch on working in War Studies at King’s College London. The post is a few years old and the department has grown, but it’s worth a read if you’re thinking about applying. (Our department is awesome- ask anyone.)

Deadline: 20 March 2016. Interviews in April.

Lecturer in War Studies (International History)

Lecturer in International Relations (Diplomacy and Foreign Policy)

Lecturer in War Studies (History and Grand Strategy) (2 years)

Defence Studies Department, King’s College London (Shrivenham campus, 1 hr outside London)

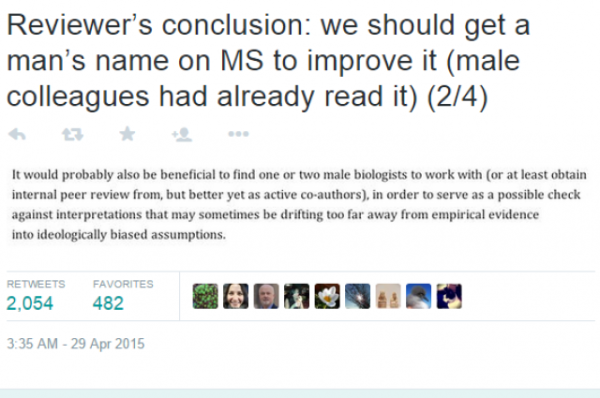

Last week, there was a big scandal at PLoS One (a major science journal) for some very sexist comments that were made as part of the peer review process. Retraction Watch wrote a nice summary on this. (For twitter commentary, see #addmaleauthorgate.)

Last week, there was a big scandal at PLoS One (a major science journal) for some very sexist comments that were made as part of the peer review process. Retraction Watch wrote a nice summary on this. (For twitter commentary, see #addmaleauthorgate.)

Personally, I was floored by how openly sexist the comments were. Usually, sexism is much more subtle- it’s more about things that don’t happen: third author, not first; section chair, not keynote speech; secretary, not president.

John Gill, the Editor of Times Higher Education invited me to respond to this scandal through a Letter to the Editor. I’ve posted it below.

This is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to gender inequality in higher education- A few examples that come to mind immediately: clear biases in Citation Practices (in international relations, in sciences), Teaching Evaluations, Letters of Recommendation, and Lower Starting Salaries. For a statistical snapshot of the problem in the UK, see Anna Notaro’s piece. More controversially, I would argue that the darker problems of rape culture in the US and Canada, and laddism and harassment in the UK, are related manifestations of how society and its institutions deal with gender inequality.

But clearly, the problem of gender inequality is not limited to universities and colleges. It persists globally, in just about every field, and pervades more aspects of our lives than we’d care to admit. Some will read this scandal as an isolated incident, but I assure you, it is not. There is now a fair amount of hard evidence demonstrating that sexism is systemic. Whether it is conscious or subconscious is debatable- but it is definitely systemic.

#AddMaleAuthorGate only scratches the surface of an inequality that runs very very deep- even then, you will only see it if you choose to look for it. And therein lies the problem- most of us don’t want to see it. Including me.

For the first two decades of my life, I genuinely believed that gender inequality was a dying problem. When I was 18, I laughed at my mom when she told me that I would eventually hit a glass ceiling in my career. I was convinced that by the time I was old enough to enter the workforce, discrimination against women in Canada would be in its twilight years- extinct, like the dinosaurs.

Since that conversation with my mom so long ago, I’ve come to realize that culture and norms are powerful things. Gender inequality is structural, sociological, biological, political, geographical, cultural. It is embedded into the social fabric of our societies, and it will take generations for big changes to take root. In the meantime, here’s my small contribution:

Inexcusable sexism calls for action

7 May 2015

The sexist nature of the peer review comments (suggesting that a paper written by two female researchers ought to include at least one male author to make sure that the data are interpreted correctly and saying that only men have the personality necessary to make it to the top jobs in science) that were offered in response to Fiona Ingleby and Megan Head’s Plos One journal submission on gender inequality in the life sciences has been met with a roar of public outrage (“‘Sexist’ peer review causes storm online”, 30 April).

As a female academic, I personally found some of the sexist comments (such as only men have the personality necessary to make it to the top jobs in science) so outlandish that it was difficult to take them seriously. Surely no credible scientist could honestly believe that it is physical stamina that explains men’s publication advantage? That the journal editor(s) accepted such a review without challenge was equally galling.

If these comments were indeed meant to be taken literally, let me ask, rather provocatively: is this a case where the reviewing scientist is so patently sexist that s/he should be unmasked in this particular instance – as a public service to the scientific community? Anonymity plays a very specific function in the research process; when it undermines trust in the system of how work is judged, as demonstrated in this case, should it be withdrawn?

I do not ask this question lightly, but rather because we (myself included) often stand by and tolerate quiet sexism within the walls of academia. If this person is evidently biased, then why are we, as an academic community, protecting such clearly sexist behaviour? If key gatekeepers (such as peer reviewers at major journals) are permitted to express their damaging personal biases without any personal cost to their reputations, then it undermines the trust of female scientists in the fairness of the overall “meritocratic” system. This sense of fairness, by the way, has already been systematically undermined in more ways than a letter allows me to express.

Christine Cheng

Lecturer in war studies

King’s College London

@cheng_christineThis piece was first published in Times Higher Education on 7 May 2015.

Many of my students in the MA in Conflict, Security, and Development at King’s College London have come directly from the policy world. They are diplomats, military commanders, NGO workers, social activists. They bring with them diverse knowledge and skill sets to the classroom, but they also bring with them particular ways of communicating that are very different from what is required of them in academia. Key to this is academic writing.

For people who worked as practitioners, it is hard to understand what could possibly be more important than deriving policy recommendations from a piece of writing. What is the point of writing about something if you can’t decide what to do about it? This is a common complaint of academic writing.

The first thing practitioners should appreciate is that deciding what to do is not the goal of an academic essay or article. The goal usually has to do with understanding the nature of the problem. With a proper diagnosis/analysis/explanation of the phenomenon, policy recommendations will follow.

So, how can practitioners-turned-students learn to write academically? The key point that needs to be appreciated is that what matters is not the impact of the argument on the real world, but rather, how this argument impacts upon the existing literature. The foundation upon which an academic essay is constructed is the literature.

First you need to build comprehension. Start your academic writing journey by reading deeply and understanding how the literature fits together. How are the debates constructed? On what ideas do they build? Where are the agreements and disagreements? How are leading thinkers grouped? What are the big ideas? You need to synthesize these ideas for yourself to figure out what fits where and who is arguing against whom.

Once you fully grasp the importance of the literature, the next task is to mimic the form. The goal here is to learn to write academically (tone, style, word choice, format, methods, presentation style, terminology, citation practices). This is like learning the grammatical rules of a new language. The goal is to look and sound like others in the discipline. If you are writing a sociology paper, you want your work to mimic the way that other sociologists write.

Once you’ve mastered the form, then you need to be able to meaningfully ‘engage with the literature‘. What does that mean? Well, you have to be able to play with it, to dance with it, to critique it, to comment on elements where you agree and disagree. When you’re able to do that, then you’ve found your ‘voice’ and you should put your own ideas into this form.

Once you’ve mastered the form and learned how to engage, you can subvert academic form- if you want. This is the fun part. Now, you can disregard the rules- up to a point. Having developed the confidence to express your ideas in your own style, you can start to improvise, and decide whether you’d like to continue using existing formats, or whether you’d like to create hybrid forms, or whether you’d like to create your own forms of academic expression.

Think about Picasso. He first had to learn classical drawing techniques. He began by copying traditional forms. Then he had to master them, and find his own style within a classical tradition. Finally, he was able to question existing forms, and discard them in order to create new styles and modes of expression.

To recap:

1. Build comprehension.

2. Mimic the academic form of your discipline.

3. Engage with the literature and find your academic voice.

4. (Optional) Experiment with new forms of expressing your ideas.

Buhari’s win- A watershed moment in Nigerian politics

Today’s election win for Muhammadu Buhari is a watershed moment in Nigerian politics. The results deserve comment because Nigeria was at a crossroads- and it seems like the citizens made a decision that is going to benefit not just Nigeria itself, but African politics as a whole.

Since Goodluck Jonathan officially took power in 2010, he has run Nigeria into the ground. For a taste of these problems, there has been the firing of central banker Sanusi, the mishandling of the Chibok kidnappings, the government’s incompetence in dealing with Boko Haram, and the staggering corruption problems within the Jonathan administration, including $20 billion that went “missing from the account of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation, NNPC.”

I never thought I would say this, but I’m actually happy that a former dictator has won this contest fair and square (thanks to new biometric voter’s cards). Here’s why it’s good for Nigeria, and good for African politics:

1. Nigeria now has a viable opposition party. This will hopefully mean a more inclusive, and more stable political system.

“This is the first time an opposition party with a diverse national support base has taken on an incumbent party: it is the end of a long period of elite pacts in national politics,” said Africa Confidential. This is extremely significant because there has long been a power-sharing pact in place within the ruling People’s Democratic Party (PDP)- this saw the Christian south and the Muslim north alternate the presidency every four years. This was an informal elite pact and voters in each region stuck to the rules of the game- for a period. Then in 2010, when Umaru Yar’Adua, a Muslim northerner, died part way through his first term and Goodluck Jonathan formally assumed the presidency.

The election of Buhari has ended this pact and proven the viability of an opposition that can harness widespread geographical, ethnic, and religious support. In this way, it becomes an important step for consolidating democracy.

2. Jonathan’s willingness to give up power signifies that he is not above the rule of the people, and that he respects the election results, even when these rules don’t work out in his favour.

It will be the FIRST time in Nigeria that an incumbent president will have lost to an opposition candidate. This is a rare moment on the continent- we have just witnessed a relatively peaceful election, followed by a graceful admission of defeat from an incumbent. Watching Jonathan concede is critical to democratic consolidation not just in Nigeria, but across Africa.

To get a feel for how truly momentous this was, read Yetty Williams’ Huffington Post piece:

Up until now, the average Nigerian was not sure whether his or her vote really counts, wondered whether votes can actually make a difference or cause a change. Till this most recent elections majority of the nation had only heard about the idea of free, fair and violence-free elections….There are people still in shock that change happened! We were able to vote out the sitting president and guess what? The sky is still intact. Life is going on! And to top it off our outgoing president called the president elect to concede prior to official announcement of the results…We are suddenly in a new era, an era where the old are hopeful that things can actually change in their lifetime — free and fair elections… Can I repeat, it was largely violence-free, free and fair — we do not take this for granted.

3. If anyone has a chance of changing Nigeria’s culture of corruption, it is Buhari.

Several years, I attended the UN Convention Against Corruption conference. I met a civil society leader there who told me about General Buhari’s rule in 1984-85. At the time, what I found fascinating was that he seemed to imply that there was a brief ordering of society. He told me that people started queuing up for buses, and that petty corruption seemed to have briefly plummeted. Until Buhari left office. Then it went back to business as usual. This civil society leader recognized that there were a lot of problems with Buhari’s rule (see his human rights record), but corruption was not one of them.

Fast forward several years to a recent Wilton Park conference on African peacekeeping: What was interesting was listening to the Nigerians express their appreciation for Buhari’s clean record when it came to corruption. My sense is that a good part of Buhari’s election win was due in part due to this contrast between a Jonathan government that has been perceived to be extremely flashy and corrupt, and the relatively modest lifestyle that Buhari has consistently lived (and has promised to maintain). Buhari, hardliner though he is, has been pretty honest about who he is, and what he has accumulated. That is rare in a country of political leaders who are renowned for corruption.

And if you believe Sarah Chayes’ thesis on how corruption contributes to the conditions that drive religious extremism, then Buhari may be also be good for dealing with Boko Haram- but not in the way that the West thinks. In searching for purity and consistency, Boko Haram has argued that the West is a corrupt and contaminating influence- if Buhari shows that he will not live the flashy life of previous leaders, then Boko Haram loses an important narrative for driving recruitment.

The right leader can have a transformative effect for a country (Mandela), a cause (Martin Luther King), or even a religion (Pope Francis). Without wanting to set expectations too high, it’s the first time in a long time that I’ve felt this hopeful about Nigeria’s political prospects. It’s been less than 24 hours since the election, but I’m already hoping against hope that Buhari doesn’t disappoint.

Women in Frontline Combat Roles

On Friday 19 Dec 2014, I talked to the BBC about allowing women women to take on frontline combat roles in the UK military. The Ministry of Defence has been reviewing its policy on this matter, and the BBC asked me for some thoughts on this issue. For a whole variety of reasons, I think women should be allowed to take on combat roles.

I have a lot more to say about this topic- hopefully I’ll be able to expand on some of the points from the clip when things are less busy. But to begin this conversation, I’ve posted the BBC interview clip below.

Some of my ideas are also summarized here in this Independent article.

Academia, Incentives, and The Secret to Unleashing Intellectual Capital- Responding to Nicholas Kristof

In the New York Times, Nicholas Kristof has just thrown down the gauntlet for academics:

Some of the smartest thinkers on problems at home and around the world are university professors, but most of them just don’t matter in today’s great debates.

Academics used to matter, but they don’t matter as much as they used to. The question is why? I think there are three sets of reasons. Partly, this has to do with the incentives within professional academia, partly it is related to the recruitment pool for academics, and partly it has to do with the ever-widening range of non-academic sources of deep knowledge that has been made accessible through new technology (think tanks, rise of NGOs, blogosphere, free access to high quality information). I’ll say something about the first two since the third is pretty obvious.

Incentives Within Academia

The core problem is one of incentives within academia: Academic prestige/tenure/promotion is based purely on publications. On the surface, this seems like a fair way of gauging merit. But it means that everything else that professors do tends to run a distant second (teaching, administration and service, public engagement). Given the fierce competition for academic posts these days, no one is going to give up their research time for public engagement (unless s/he enjoys doing it) if they don’t already have tenure. (For adjunct professors/temporary lecturers who live from paycheque to paycheque with no job security, the situation is even more precarious. See Corey Robin’s excellent post on this aspect of the problem.) Writing specialized journal articles will win every time because our careers depend on it.

“Many academics frown on public pontificating as a frivolous distraction from real research,” said Will McCants, a Middle East specialist at the Brookings Institution. “This attitude affects tenure decisions. If the sine qua non for academic success is peer-reviewed publications, then academics who ‘waste their time’ writing for the masses will be penalized.”

If the powers that be really want public engagement then they need to explicitly include this in their criteria for tenure & promotion. Even requiring a token op-ed in a newspaper would send an important signal. Of course, there is the caveat that public engagement is not relevant for all disciplines or within a discipline- but for disciplines like politics, you would think that most of us would want to engage with a wider audience beyond the boundaries of specialized journals.

The Recruitment Pool for Academia

Regarding who is most likely to become an academic these days, there are a couple of important trends. First, in my own discipline of politics, fewer “public intellectual” types are being drawn to academia than used to be the case. Instead of doing a PhD, many of these people are joining think tanks, opting to work for NGOs or international organizations, heading to tech start-ups or management consultancies, or occupying the social entrepreneur space. These are options that just didn’t exist twenty years ago. The bottom line is that many of those with the inclination and the smarts to become academics have chosen to do other things now that there are so many interesting (and well-paid!) career options. Second, the culture of politics as a academic discipline has also changed significantly in the past twenty years.

A basic challenge is that Ph.D. programs have fostered a culture that glorifies arcane unintelligibility while disdaining impact and audience. This culture of exclusivity is then transmitted to the next generation through the publish-or-perish tenure process. Rebels are too often crushed or driven away.

If you think about academia as an exclusive club that many, many people want to join, it becomes possible to see that key gatekeepers (journal editors, tenured faculty at the Top 10) hold a lot of power. If gatekeepers want to set an exclusive and difficult-to-penetrate research agenda for the discipline, they can readily do so in choosing the kinds of articles that get published in top journals, the kinds of PhD projects they are willing to supervise, and the kinds of work that they consider to be “groundbreaking”. This isn’t just about rebels being crushed or driven away, as Kristof alleges, but rather that the rebels are no longer drawn to academia in the first place because the kinds of narrow research questions that are being asked today don’t excite them. Further, the pressures to publish can be severe enough that if your research falls outside of disciplinary norms, your work risks being marginalized- with all of the consequent career implications. Namely, you’re highly unlikely to make it into the profession in the first place. These dynamics shift the academic recruitment pool in a certain direction. [See this post comparing academia to drug cartels from a King’s colleague, Alexandre Afonso.]

Academic Superstars & the Hyper-Engaged

For younger scholars, I would say that even though Kristof is mostly right about the broad lack of public engagement, he has also omitted the story of the superstar academics. Just within the realm of politics and international relations, Twitter, MOOCs, the blogosphere, and TED talks have created academic superstars out of people like Anne-Marie Slaughter, Chris Blattman, Daniel Drezner, and Saskia Sassen. I can also name dozens upon dozens of hyper-engaged academics who blog, tweet, and engage in policy-making. (Here are just a few: Laura Seay, Lesley Warner, Roland Paris, Severine Autesserre, Susanna Campbell, Rob Ford, Thomas Rid, Lawrence Freedman, Jeff Colgan, Stephen Saideman, Jennifer Welsh, Dominik Zaum, Jeni Whalan, Daniel Drezner, Lee Jones, never mind widely read blogs like The Monkey Cage, Political Violence at a Glance and Duck of Minerva. The list goes on and on. Did I mention that half of my department at King’s is active on Twitter?)

As with the rest of the labour market, those who go the extra mile to engage publicly will mean that they can reap the reputational returns on a global scale. For these hyper-engaged academics, the rewards are more likely to come in the form of public and disciplinary influence rather than pay increases.

Academic Rigor and Relevance

A few more thoughts: I don’t think you need to give up academic rigor in order to do interesting, accessible, and relevant research. We shouldn’t conflate rigorous with being inaccessible/uninteresting/irrelevant. There does not need to be a trade-off here as implied by Rubin Ruiz-Rufino. The problem may be more in how “rigorous” is defined- an altogether separate discussion. Disciplinary “rigor” could still mask other problems:

After the Arab Spring, a study by the Stimson Center looked back at whether various sectors had foreseen the possibility of upheavals. It found that scholars were among the most oblivious — partly because they relied upon quantitative models or theoretical constructs that had been useless in predicting unrest.

Separately, we need to gauge “relevance” with caution. Just because a subject is obscure today does not mean that it should not be studied nor does it mean that the quality of scholarship is poor. Way back in 2000, how many politics scholars in the West could even pick out Afghanistan on a map, never mind offer us insights into Afghan politics, culture, and society? Afghanistan was about as obscure a subject as you could imagine, and yet Barnett Rubin had persisted in following Afghan politics for decades…. Another example: Back in 2007, Shadi Hamid presented his doctoral project on the Muslim Brotherhood at Nuffield College’s Graduate Politics Seminar in Oxford. At the time, it seemed like an interesting if slightly obscure topic. And then came Tahrir Square.

If obscurity is not the problem, neither is the impenetrability of the discipline in and of itself (as Steve Saideman argues here). The problem is the MIX. Right now, the obscure and impenetrable seem to dominate many of the discipline’s key institutions. As I said to Steve, I think that rigor is still being prized over relevance. In short, it is more advantageous to formulate an airtight argument to a narrow and mildly interesting research question rather than to offer a thoughtful (but not airtight) argument to a much more compelling question. [Interestingly, I think the gap between academia-policy-public is much smaller in the UK as compared to North America.]

Unlocking Academia’s Intellectual Capital

While my sense is that younger scholars in my discipline of politics are happily engaging more with the public via social media and other forums, it’s clear that there is a tremendous amount of intellectual capital that is trapped within the ivory towers because the incentives aren’t strong enough to unlock it. For politics departments, I have one small recommendation: Require extended abstracts for all publications that are submitted as part of tenure and promotion/probation processes. Ask for 750 word executive summaries with key findings in layman’s terms. This minor addition would make scholarly studies much more useful and readily accessible without changing what people study or how they decide to study it. In the long run, this is the kind of change that will tilt the balance in favour of public engagement and put politics scholars back at the heart of public discourse- where they belong.

Remembering December 6th and the Montreal Massacre

I wrote this email when I was 23 years old, in my final year of my systems engineering program at the University of Waterloo. Even though the Montreal Massacre happened so long ago that many of you may not have even heard of it, I hope that we can still take the time to remember the women who were killed, simply because they were women. Let those fourteen young women never be forgotten.

From The Daily Bulletin, circa December 4th, 1998:

After our conversation last week, I sat back and thought long and hard about what we’re trying to do with this event, because like it or not, it has become an “event”. The members of the organizing committee are trying to de-politicize it by making it personal, but we can’t deny that it is a public event for a reason.

1989 seems so long ago . . . that was the end of Communism and the height of the real estate boom. Nine years later, here we are: so much has changed and yet, nothing has changed. You said to me that it seemed like just yesterday that the killings took place, but nine years is a long, long time. Especially when you’re only 23, like me. I was 14 years old and in grade nine on December 6, 1989. I did not completely understand the killings and why they had happened. I had no idea I would end up, five years later, studying to be an engineer. And for those of us in first year at UW, these students would only have been 9 years old, and in the middle of grade 5 — how can you relate to this experience at this age?

I understood at the time that the gunman was a sociopathic killer, but I had no explanation as to how this could have possibly happened in the world that I had grown up in. His irrational behaviour didn’t fit into my model of how things worked and I had no reason to think of him as anything other than an extremist, someone who would not and could not listen to reason. My solution was to exclude him from my world, to cast him out. I guess this also meant that, to some extent, I ignored the impact of what he had done and the hatred that he represented. There was nothing in my social conditioning that allowed me to understand his deep-seated despisal of women, and in particular, of feminists.

Now, nine years later, I have a slightly better sense of the methodically rational side of his actions. After all, it was not in a rage of passionate fury that he committed these murders. A virtual hit list was found on his body consisting of fifteen high-profile women: these included the first woman firefighter in Québec, the first woman police captain in Québec, a sportscaster, a bank manager and a president of a teachers’ union.

Society recognizes that he was a psychopath — but to what extent was he a product of social influences, and how much of it was sheer and utter isolated madness? The two of us talked about the continuum and where this event would sit on this continuum. I don’t have an answer for this. What I do know is that it was and still is, to a greater or lesser extent, a reflection of society’s attitudes towards women.

So we must ask ourselves: How do these attitudes filter down through the rest of society? When a male classmate jokingly says to me that I won my scholarship because I am female, how am I supposed to interpret that? How does that relate to the fact that the killer felt that these women got into engineering because they were female? He certainly felt that they were taking up his “rightful” place in the program. Am I taking up the “rightful” place of another disgruntled male in systems design engineering?

He committed an extreme act, but society is at a crossroads right now — we value women’s equality, but the lingering effects of centuries of discrimination is not going to disappear overnight and we have to recognize that together. We are valued in the eyes of the law. But in practice, systematic discrimination still goes on, even if it isn’t as obvious as it used to be. Women are not equal. If we were, everyone would understand that December 6, 1989, was just an aberration, a blip in the stats. But obviously, the need for an event like Fourteen Not Forgotten implicitly underscores the fact that there are many of us who still harbour a milder version of the killer’s views. How else to explain the fact that women are more likely to be killed by their spouses than by an outsider?

Also, we have to remember that fourteen women were killed, but hundreds, maybe thousands of people were affected, men and women. What could my male classmates have possibly done if I was being shot at? Not too much. And how can we accept this conclusion: that we are helpless in the face of irrational evil? That is why we remember December 6. Hopefully, by speaking out against these attitudes and these acts of violence, we are helping society address these issues to make sure that it never happens again. Men and women who survived the massacre still have to bear the burden of the death of their classmates. These people will live in fear all their lives. How do we collectively deal with that? What about when these fears are conveyed to their children and grandchildren? All it takes is one gunman to spread his hatred, and the effects are felt far and wide. This memorial is, in many ways, a show of solidarity against everything that killer stood for. That is why we mourn, and why we must continue to remember.

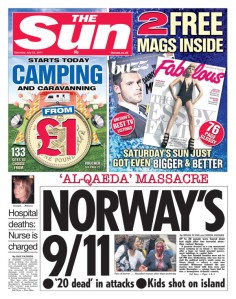

Charles Taylor and the logic of relative justice

A version of this article was first posted on Al Jazeera on 26 September 2013.

Yesterday, the Special Court of Sierra Leone upheld Charles Taylor’s conviction for aiding and abetting war crimes in Sierra Leone’s civil war. The Appeals Chamber also rejected his request for a reduction in his 50 year sentence, pointing out that he had not shown ‘real and sincere remorse’ for his actions. On the face of it, this decision appears to be another victory for transitional justice: the international community succeeded in locking up another brutal dictator, and now, it has also thrown away the key.

For those who follow international war crimes tribunals and the workings of the International Criminal Court, the Special Court’s decision would not have come as a surprise. On the one hand, it was certainly theoretically possible that the Appeals Chamber could have set Taylor free by adhering to the precedent in the Momčilo Perišić case. Yet this outcome seems fantastical in light of the political context in which this seven-year trial has taken place. The conclusion was foregone before the ink was even dry on the appeal documents. The reason is simple and has nothing to do with the merits of the case: A free Charles Taylor would have entailed too many risks to the region.

After many years of civil wars and border skirmishes, Liberia, Sierra Leone and Côte d’Ivoire are finally stable. For the moment. As the driving force behind the region’s conflicts through the 1990s and early 2000s, setting Taylor free could have upset the fragile balance in West Africa. Even though Liberia’s civil war ended over a decade ago in August 2003, Charles Taylor remains a powerful force in the country- despite not having set foot on Liberian soil since 2006. The Special Court could not afford to let him go free, not without the possibility of risking Liberia’s security and undermining the integrity of the tribunal itself.

Still, it would be unfair to say that the Appeals Chamber is not impartial. There is no evidence that this is the case. The justices appear to be qualified and of international repute. Nevertheless, as independent as the judges themselves may be, they are appointed by political bodies with political interests. Valerie Oosterveld shows how deeply political considerations affected many critical aspects of the Special Court, from the drafting of the SCSL’s statute to its judgments to its decision to physically close the court. It would be naive to think that any shortlisting process of the Appeals Chamber justices would not have been shaped by these political dynamics, or that the justices themselves would be unaware and unaffected by the desires of those who appointed them.

In fact, we already know from the work of Ruth Mackenzie, Kate Malleson, and Philippe Sands that selecting judges to international tribunals is a fraught process. Ultimately, Sands has asserted that ‘the horse-trading and politicking is endemic.’ He also claims that ‘vote-trading, campaigning, and regional politicking invariably play a great part in candidates’ chance of being elected than considerations of individual merit’. While their study was conducted on the International Criminal Court and the International Court of Justice, there is no reason to think that the same political dynamics would not hold true of the Special Court for Sierra Leone.

Bear in mind too that the Special Court received most of its funding from the West (US, UK, Netherlands, and Canada), and Western countries have contributed billions of dollars in humanitarian aid and reconstruction to the region. In addition, the UK has offered Sierra Leone an ‘over-the-horizon’ security guarantee. Effectively, this means that the UK is committed to responding to a national security incident within 72 hours. Given these considerations of national interest, it is hard to imagine how the desires of the UK and the US would not have influenced the environment of the court. Keeping larger political influences and geopolitical considerations at bay in a case like this would have been near impossible.

Westerners might wonder how any of these factors could affect the final decision of the justices. After all, justice should be blind. And yet, we can see that it is not. None of these revelations would surprise Sierra Leoneans and Liberians. In Africa certainly, war crimes tribunals are widely acknowledged to be deeply politicised institutions. In fact, the African Union has recently called a special summit to discuss a mass withdrawal from the ICC in October because international justice is seen as baldly biased against Africans.

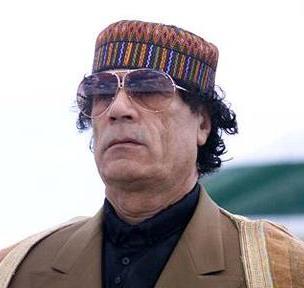

I have argued elsewhere that the ICC is perceived by many as a tool of Western powers. Other UN-backed tribunals also suffer from this problem, including the Special Court of Sierra Leone. Others have made similar arguments. Guardian columnist Seumas Milne has asked why Western leaders have not been indicted for aiding and abetting war crimes when they too supplied arms and assistance to Libyan militias in the fight against Gaddafi— just like Charles Taylor did for Sierra Leone’s rebels. International legal scholar Richard Falk has questioned why American leaders have not been charged for the systematic abuses that have been widely documented at Guantanamo Bay and Abu Ghraib.

The facts are clear: justice is applied selectively depending on what country you are from and whether you are in favour with the West. By nudging, suggesting, and sometimes coercing international courts to serve political interests, Western powers manage to achieve desired political outcomes. But these tactics are putting delicate norms of transitional justice at risk.

If international war crimes trials are ever to achieve genuine global justice— for the weak as well as the powerful— there must be some acknowledgement that these tribunals are currently being used as political instruments of the powerful. Only when this premise is accepted by the West can the ICC evolve into an institution with real international legitimacy.

War Studies is hiring a Lecturer in Conflict, Security, and Development for a fixed-term of 3 years.

Deadline 20 June 2013

This is basically an assistant professorship without tenure (US translation)/fixed-term lectureship. The practical details are still being ironed out though. Please forward the link to anyone who might be interested.

I can say wholeheartedly that as a junior faculty member, my King’s experience has been fantastic so far. Here is the CSD group: Mats Berdal, Oisin Tansey, Domitilla Sagramoso, Kieran Mitton, and me. You couldn’t get a nicer bunch of people, and this group is pretty dynamic in terms of research.

While there is a bonanza of politics lectureships this year, I suspect that there will be a drought for a year or two in the aftermath of the REF. The hidden bonus of this position is that this job will take you out past that lean period.

For more on why you should apply, see here for my sales pitch on working in War Studies at King’s College London. Note that this is a 3-year lectureship, not a permanent lectureship.

Ok, it doesn’t always look this spectacular.

Full job description and application information HERE.

The Department is looking for a distinguished scholar who already has an outstanding profile in the field of International Relations with a general focus on Conflict, Security and Development. It seeks applicants who have a publication list that includes both monographs and peer-reviewed articles in leading scientific journals. The successful candidate will be expected to strengthen the War Studies Department’s teaching and research capacity in relation to one or more of the following crosscutting themes.

• The Political Economy of Civil War and Post-Conflict Peacebuilding

• Post-Conflict Democracy Promotion

• Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Aid

• State Failure and Fragility

• Politics, Conflict and War in Africa

• The UN and its specialised agencies, programmes and funds

• Regional organisations with a special focus on Africa

• Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration of combatants (DDR) and Security Sector Reform (SSR)

• Natural Resources, Scarcity and conflict

• Development and Aid during and after Violent Conflict

• The Bretton Woods institutions and Post-conflict reconstruction

• Donor Politics

• NGOs and Private Sector Involvement in Reconstruction

The successful candidate will be expected to complement the work undertaken by one or more of the following research groups within the Department: Africa Research Group and/or, The Conflict Security and Development Research Programme.

The successful candidate will be expected to make a major contribution to teaching on the MA in Conflict, Security and Development. He/she will also be expected to make a contribution to teaching on BA War Studies and on the Department’s MA programmes. Finally, the person sought must have a proven ability to initiate and lead research projects, together with a commitment to launching new ones. The person appointed will be expected to carry his/her share of administrative duties within the Department.

The post will be based at the Strand campus.

The appointment will be made, dependent on relevant qualifications, within the Grade 6 scale, currently £33,654 to £39,705 per annum pro rata, inclusive of London Allowance.

[Note that you will only be paid 80% of this!]

Sept 2013 to June 2016

Interviews on 2 July.

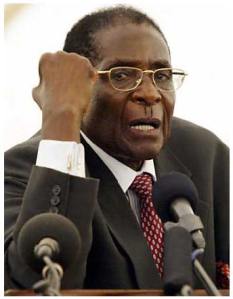

Nostaglic for Jean Chrétien

This week, I stopped in Toronto briefly on my way home from a conference, and as I often do, I invited my friend John English out for a coffee. It just so happened that he had co-organized a major conference at the University of Toronto on the legacy of former Canadian Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson. He invited me along.

The program was packed with prominent Liberal leaders, past and present (Bob Rae, Allan Gotlieb, John Turner, Lorna Marsden). [John happens to also be one of the most famous Canadian historians around and a former MP which makes it easy for him to do this kind of thing.]

I arrived at the end of the day’s program, just as former PM Jean Chrétien was about to take the stage with former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Bill Graham. Chrétien had decided to do a Q&A session with the audience rather than a more formal interview with Graham. At that moment, I knew that this was going to be fun- our former PM had just changed the format to encourage audience interaction. Whereas politicians in office inevitably give scripted speeches with no surprises, ex-politicians are usually pretty frank about their experiences. And Chrétien was no exception. [Get them over dinner after a few glasses of wine, and the stories get even more interesting.]

Here are a few things that he talked about that I thought were worth sharing:

[Please note that I’ve paraphrased and changed the order in which he made his comments.]

On politics and Canadian values:

Don’t be too strategic. Do what is right. The votes will follow. Do what you feel good about. The debate is about values.

We [Canada] were extremely respected. Generosity, respect for minority. These were values that everyone wanted to copy. We were always ahead of many countries on many issues.

On not going to war with Iraq, and breaking with our closest allies on foreign policy:

I knew that Saddam had nothing to do with 9/11.

[Chrétien to Bush] The policy is not to be with you if you don’t have the support of the UN.

Bush offered to brief Chrétien. Chrétien said that this wouldn’t be necessary- he had been briefed by his own people. He told Bush: For the UN, you need better proof of WMD. I’m not convinced.

After many years as PM, Chrétien was treated as an elder statesman on the UN Security Council. Other countries and leaders were consulting him. Bush was particularly unhappy with Chrétien because Mexico and Chile had decided to follow Canada’s lead.

[Chrétien to Blair] Saddam and Mugabe are not the same. If you have the UN, I might be able to go. You need to convince George to go to the UN.

Blair had urged him to go to Iraq to get rid of Saddam Hussein. Bush was talking about WMD. Chrétien said to him: “I don’t want to be in the business of replacing people that we don’t like.”

On the social community of parliament:

Chrétien also spoke of how the social dynamics of parliament had changed. He described how politicians used to make their home in Ottawa and that there was much less travel back to MPs’ ridings. There were many consequences of this practice, but one was that politicians from all parties formed a community. Their children went to school together; they ate together; and they socialized together. [They probably also drank brandy and smoked cigars together while their wives put the kids to bed- but that’s another story altogether.] Political fights didn’t get personal.

On the role of TV:

He talked about how allowing television cameras in the House of Commons wrecked the collegiality of parliament. He lamented how relationships with colleagues changed as soon as the TV cameras were switched on.

Old school politics:

One last thing that I hadn’t quite appreciated was how parliament had become less spontanenous over the years. (Chrétien was first elected to parliament 50 years ago.) Politicians used to be expected to speak off-the-cuff. They would make just a few notes for a speech in the House. Reading your speech would have broken a social norm, never mind hiring a speechwriter to write your speech for you. Chrétien said that it was simply “not allowed”. On a more practical level, two MPs used to share a personal assistant between them, and the resources just didn’t exist for anything fancier.

* * * * *

All of this made me nostalgic for the days of Jean Chrétien- when Canada was doing both great and good things in foreign policy and at home; when our economy was in order; when my government was projecting values that I was proud of. And then, just as I was bathing in the afterglow of Canadian goodness, my political conscience spoke up and I remembered the sponsorship scandal. And yet…. I couldn’t help but long for the Chrétien days.

How to square that circle- especially since I spend a fair amount of time railing against corruption? Well, after many years of following politics in the news, meeting politicians, and studying politics, here is what I’ve realized: dig deep enough into any seasoned politician’s past and you will find skeletons. (Or at the very least, severe compromises in her principles.)

The longer her time in politics, the more skeletons there are likely to be. Those who have no skeletons are the ones who are the most principled and the least likely to make compromises and do deals. They are also the ones who are least likely to be re-elected. Think Mulroney on Airbus, Obama on Guantanomo and soft money, or in this case, Chrétien on AdScam. I could go on.

Call it the principle of political Darwinism- only the compromised will survive. Without wanting to seem fatalistic about politics in general (in case my students mistake me for a cynic), I’ve just decided to accept the bad with the good, and enjoy what is left of that golden era of Canadian politics.

Defending Romney’s “Binders Full of Women”

This piece was first posted on Al Jazeera on Monday 22 October 2012.

Politicians say stupid things all the time. The comment that has caught American attention for the past few days was Mitt Romney’s reference to “binders full of women” during the second presidential debate.

To put the remark in context, Romney was answering a question about equal pay for women (which he skirted) when he began talking about the early days of his administration as governor of Massachusetts and his efforts to incorporate more women into his cabinet.

He said: “….I went to my staff, and I said, how come all the people for these jobs are — are all men? They said, well, these are the people that have the qualifications. And I said…can’t we find some — some women that are also qualified? And — and so we — we took a concerted effort to go out and find women who had backgrounds that could be qualified to become members of our cabinet. I went to a number of women’s groups and said, can you help us find folks? And I brought us whole binders full of — of women.”

Although his choice of words was slightly cringeworthy, it was clear what Romney was trying to say: I don’t just preach inclusion, I practise it too. But his comment sounded off-key and just a bit desperate. It sounded like the only place he would have been able to find any qualified women was in these binders. To draw a crude analogy, he seemed to be shopping for a female cabinet minister the way some men might shop for a mail order bride.

Normal people were left wondering why a corporate titan like Romney would have to resort to a binder to find qualified women. As David Bernstein points out, shouldn’t he have been surrounded by smart and ambitious women through his years in the business world and from his political campaign? It led me to wonder: why were these women so difficult to find in Romney’s world?

On the surface, this appears to be the reason why his comment was so gaffe-worthy. But those who support gender equality ridicule his comments at their own peril. (Mea culpa, I include myself here.) Despite the unfortunate language, the intentions underlying Romney’s comment about binders full of women should be applauded, not derided.

Although it turns out that Romney did not ask for the binder of qualified women but was instead given it by MassGap, a bipartisan coalition of women’s groups, the fact remains that he used that binder it exactly as MassGap intended it to be used. He referred to it in appointing outstanding female candidates to senior leadership positions. This was affirmative action as it was meant to be practised.

Romney even boasted in the next breath that “after I staffed my cabinet and my senior staff… the University of New York in Albany did a survey of all 50 states and concluded that mine had more women in senior leadership positions than any other state in America.”

Romney should be praised, not chided, for doing with that binder precisely what women’s organizations wanted him to do. He could have tossed that binder straight into the garbage can. The fact that he was proud of having so many women in his cabinet has not gotten nearly as much attention as it deserves.

Having had a few chuckles at Romney’s expense over the past few days, let’s recognize that MassGap’s Binder Full of Women was actually an effective way for him to search for qualified female candidates. After all, we don’t mock organisations like Women In International Security when it assembles its portfolio of renowned female security experts. Nor do we laugh when the BBC works with findaTVexpert to add more women to its roster of television experts. Nor are we tripping over ourselves to make fun of MassGap itself.

These databases of women exist because officials need to make hiring decisions quickly and efficiently. I would be surprised and disappointed if Obama did not have his own binders full of women. Instead, if we want to have a critical conversation about the MassGap binder, let’s find out who was in that binder and what policies they championed on behalf of women.

Sure, Romney could have and should have done more to promote women at Bain and during his governorship. Sure, it was somewhat embarrassing that he did not know enough talented women to fill his cabinet without consulting the MassGap binder.

But mocking Republicans for their efforts to include more women in senior government positions sends entirely the wrong message to those in positions of political and corporate power: We will lambaste you if you fail to include women in your senior ranks, but if you need to look outside your own circles for smart and talented women, we will create internet memes of you that will keep TV talk show hosts feeding on your remains for the foreseeable future.

Is this really what progressive America wants?

If Americans want to roast Romney and the Republicans for their attitudes towards women, then they should do so for the right reasons. There is no need to turn to “binders full of women” to see why the GOP has a problem with female voters.

First, Romney has pledged to eliminate federal funding for Planned Parenthood. Then there was his promise to appoint an anti-Roe justice to the Supreme Court if given the chance. Let us also not forget Representative Todd Akin’s laughably ignorant assertion that a “legitimate rape” doesn’t lead to pregnancy because “the female body has ways to try and shut that whole thing down.” And of course, Romney would have refused to sign the Lily Ledbetter Act.

These were the real reasons why the binders full of women comment struck a chord with Americans. In this Romney-Republican world, things happened to women— others made decisions for them, about them. When Romney and the Republicans realize that women can make decisions for themselves and about themselves, then maybe, just maybe, American women will start respecting the Grand Old Party once more.

After Chris Stevens: The Importance of Insider Criticisms from the Arab-Muslim World

After the killing of US Ambassador Chris Stevens, Libyans in Benghazi express concern. Photo credit: Mohammad Hannon/AP from The Guardian (http://bit.ly/VKNsJG).

In his latest column for the NY Times, Thomas Friedman highlights how moderate pundits from the Muslim world have written some very harsh, self-critical op-eds in key Middle Eastern media outlets following the assassination of US Ambassador to Libya Chris Stevens and three other Americans. These types of critical pieces are probably more prevalent than Westerners are led to believe and Friedman does us all a favour when he uses his NY Times platform to shine a spotlight on the range of views that exist across the Arab world.

To be clear, official condemnation of the Stevens murder has been universal:

The Muslim Brotherhood (MB) and its officials, the Sheikh of Al-Azhar, the Egyptian prime minister, officials in Al-Gama’a Al-Islamiyya, and even Salafi elements all called to avoid violence and harming embassies and diplomats, claiming that it is contrary to Islam; some even issued fatwas forbidding it.The violence was also condemned by the head of the International Union of Muslims Scholars (IUMS), Sheikh Yousuf Al-Qaradhawi, as well as by the leaders of the Gulf states and the Mufti of Saudi Arabia.

But there is more. The murders and the offending YouTube video that spurred the attacks has led to some provocative pieces being published. Translated by the Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI), some of these passages are worth quoting at length:

Al-Hayat columnist Hassan Haidar: The most dangerous thing is that the extremists, exploiting the Arab spring revolutions, are trying to impose themselves as the force that shapes the new regimes in their countries. They are prepared to take up arms and [act] violently to strengthen their position, while threatening not only ‘infidel foreigners,’ but also moderate Muslim citizens and Christian minorities. The fear is that their extremism and rejection of the other will cause a majority of the people [in their countries] to regret the change they supported.

Throughout the past decade, Muslims have made tremendous efforts to cleanse Islam of the terrorist image that some tried to pin on it after Al-Qaeda’s crimes in 2001. It is the responsibility of the new regimes in Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia to change the terrifying image [of Muslims] created by the behavior of extremists; to stop those trying to spread acts of extremism and intimidation before they get worse; and to prove that they belong to the tolerant middle way of Islam.”

And the harshest words of all come from Imad Al-Din Hussein in Al-Shurouq in a prominent Cairo daily:

We curse the West day and night, and criticize its [moral] disintegration and shamelessness, while relying on it for everything – from sewing needles to rockets. It is both funny and sad that we call to boycott Western goods, as though we could punish it while still relying on it. We import, mostly from the West, cars, trains, planes… refrigerators, and washing machines… We import most of what we eat… as well as all kinds of technology and weapons… Even our curricula are partially imported. And we steal ideas [from Western] movies and [artistic] works. We are a nation that contributes nothing to human civilization in the current era. We import the culture of the West, which we call infidel and curse from morning until night. We have become a burden on [other] nations…

The world will respect us when we return to be people who take part in human civilization, instead of [being] parasites who are spread out over the map of the advanced world, feeding off its production and later attacking it from morning until night. Only when we eat what we sow [ourselves], drive [vehicles] that we produce, and consume what we make – [only] then will we be [independent] of the world… When we become civilized and obey true Islam, then everyone will respect us…

The West is not an oasis of idealism. It also contains exploitation in many areas. But at least it is not sunk in delusions [and preoccupied with] trivialities and external appearances, as we are… Therefore, supporting Islam and the prophet of the Muslims should be done through work, production, values, and culture, not by storming embassies and murdering diplomats…”

As a Westerner, what is interesting about these criticisms is that these are Muslim voices. Imagine for a second that the piece written by Imad Al-Din Hussein (at the very end) had been written by Canadian or a Brit or a German. Unthinkable, right? It’s impossible to imagine because these types of criticisms could never ever be uttered in public by a Westerner without being branded a racist bigot. Some criticisms (valid or not) can only be legitimately put forward by members of that community. This insider effect is critical to how any piece of criticism is absorbed. It’s not just what is said, but who says it.

This observation is rooted in the social psychology literature which shows that the most influential political voices are actually “turncoats”- those who switched over from the other side. Former critics are best poised to convince those from the “other” side. For example, think back to Greg Smith’s scathing critique of Goldman Sachs in his public letter of resignation. Or consider Bill Cosby’s rant about the breakdown of African-American society. It’s not just the message, but the messenger, that matters.

Cass Suntein discusses these ideas in greater depth here, relating them to the polarization between Republicans and Democrats in US politics.

In short, insider criticisms can’t be dismissed as easily because:

People are most likely to find a source credible if they closely identify with it or begin in essential agreement with it. In such cases, their reaction is not, “how predictable and uninformative that someone like that would think something so evil and foolish,” but instead, “if someone like that disagrees with me, maybe I had better rethink.”

There is an important policy implication here for thinking about the relationship between the West and the Arab-Muslim world. Friedman is right: The West should be pushing for greater freedom of expression. Clearly, there is value in this freedom for its own sake. But the West also needs to create a public space that will allow more critical insiders to speak up from the Muslim world itself. Without these moderate voices, we should expect to see US-Muslim relations become more and more polarized.

The End of Men and Equality for Men

A little less that…

An interesting commentary from The Globe’s Margaret Wente on how women are better able to adapt to the changes in global economy than men are. Wente is summarizing the argument from Hanna Rosin’s new book The End of Men (reviewed by Jennifer Homans for The New York Times). There are problems with the argument, but the broad trend about middle- and working-class demographics in the US seems persuasive. In short:

Today, the things that women excel at – human contact, interpersonal skills, verbal skills, creativity – are more valuable than brawn and muscle. These skills can’t easily be outsourced. Women are good at interpreting feelings and ideas. They’re smart, diligent and reliable, and they mostly stay out of trouble. On top of that, they’re extraordinarily adaptable. Women have taken on new roles and colonized male realms (pharmacy, veterinary medicine) with astonishing speed, and held on to their old roles and realms as well.

But the men are stuck. It’s much harder for them to adapt, and a lot don’t even want to try. Few men of any age are willing to go back to school, especially if they have to clean toilets for the privilege. Even fewer are interested in “women’s” roles, even though those fields are where most of the employment growth will be. Of the 30 professions projected to add the most jobs over the next decade, women dominate 20. Many of these jobs (home care, child care, food preparation) replace things women used to do at home for free.

What happens when women start entering a male trade? That job becomes devalued (at least in men’s eyes), and men flee – a phenomenon that Harvard economist Claudia Goldin calls “pollution.”

While women’s career opportunities and earning power have clearly improved in recent decades (see Liza Mundy’s book The Richer Sex: How the New Majority of Female Breadwinners Is Transforming Sex, Love, And Family), men have ceded more economic territory to women than they needed to by refusing to work in certain industries. On the one hand, women have fought for the right to work as firefighters, as construction workers, and as soldiers. On the other hand, men have shied away from industries as they became more feminized. Somehow, our culture has signalled to men that it is not okay for men to become primary school teachers, nurses, and pharmacists.

This attitude of “pollution” permeates the US, Canada, and the UK at many levels, even for kids. Girls can dress as tomboys, but we become deeply uncomfortable if a boy puts on a dress. A young girl who cries in the playground is consoled by her dad. A young boy who cries in the playground is told to stop being such a sissy. Girls are encouraged to play with trucks, but when boys start dressing up Barbie dolls, parents get worried. We can see a lot of these concerns play out in the controversy around a Toronto couple who are raising their children to be genderless.

As women begin to colonize new service sector opportunites and make significant gains at the higher end of the economic spectrum, these types of attitudes on “pollution” will pose more and more of a social problem. Men will feel particularly squeezed because industries like manufacturing have collapsed. Through a few snide comments and some snickers about wanting to see that guy in a nurse’s uniform, we signal all sort of things about what is and is not acceptable for a teenage boy to aspire to.

That needs to change.

Here is the core of the problem: Women’s opportunities have expanded and become more flexible in the workplace and at home, and women have fought hard to gain societal acceptance for these changes. Culturally, we have made it acceptable, even desirable for women to have a choice of roles in the workplace and in their family life. In sharp contrast, the range of socially acceptable choices for men at home and in the workplace is tightly bound (though evolving). Stray outside of these boundaries and you risk ostracization.

Over the years, we’ve managed to destroy a lot of gender stereotypes about women. Now, we need to do the same for men.

* * *

Hanna Rosin’s article, The End of Men, in The Atlantic, 2010.

Humane Authority in China and the Three Houses Proposal